Confessions of a photographer

Spring is in the air! Wild garlic is shooting up everywhere, cherry blossom buds are swelling and the birds are singing with renewed vigour. On my daily lockdown walks I marvel at how growth seems to be accelerating on a daily basis – camera in hand, of course. My macro lens has been dusted down and firmly taken over the reign in my camera bag. It feels good to witness nature’s reawakening and as every year the humble snowdrop is the first to venture out.

I have been photographing snowdrops for years now and I still can’t resist their spell.

I am not the only one, snowdrops have a special place in many people’s hearts and have been immortalised in the arts – from folklore, poetry, painting, photography to jewellery and fabrics. There is even a term for these snowdrop lovers – galanthophiles – and I happily confess to being one!

So what makes snowdrops so special?

I am going to try and attempt to answer this question in part 1 of my ‘Homage to the Snowdrop’.

In a soon to follow second part to this blog I will focus on how I create my snowdrop images, many aspects of which relate to close-up & macro photography in general.

Snowdrops in evening light – I love the low, warm morning and evening light that makes the translucent snowdrop petals glow. Backlighting, photographically speaking, is perhaps the most challenging lighting to master, if you get it right, it can be one of the most rewarding, creating very atmospheric images.

Some facts about Galanthus nivalis (lat.) – the common snowdrop

The name Galanthus is Greek in origin meaning ‘milkflower’, nivalis being the adjective of neve (snow). The genus Galanthus consists of 20 species and belongs to the amaryllis family (Amaryllidaceae).

Distribution:

The Common Snowdrop is now widely distributed all over the British Isles, however it is not native to the UK and probably first escaped from cloister gardens. The species naturalised quickly and can form large white spring carpets where conditions are favourable. Although snowdrops have been mentioned in literature since Elizabethan times, the first botanical records stem from the 18th Century.

Snowdrops soon became extremely popular with gardeners and today there are hundreds of garden varieties, many filled ones among them. Some are difficult to propagate and bulbs of rare varieties can yield very high prices indeed, like a single bulb of Galanthus plicatus ´Golden Fleece`, which was sold for a record £1390.

Snowdrops became so popular amongst gardeners that large quantities of wild snowdrops were dug up and sold. As a result, they have had to be given protection under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) and it is now illegal in most European countries to dig up snowdrops in the wild without license.

Snowdrop flower with inner and outer tepels emerging out of the spathe.

Description:

The single, white flower consisting of an inner and outer ring of 3 tepals (or segments) hangs from the flower stalk. The segments of the inner ring are fused and have characteristic green markings. There are 6 pointy anthers in the centre as well as the stigma and style leading into the ovary. The flower bud is protected within the spathe (two bract like structures joined by a papery membrane). The membrane opens when weather conditions become favourable and the flower emerges hanging from a thin stalk, the peduncle.

Snowdrops emerge from bulbs which produce two or (more rarely) three linear, greyish-green leaves as well as the single flower.

Propagation:

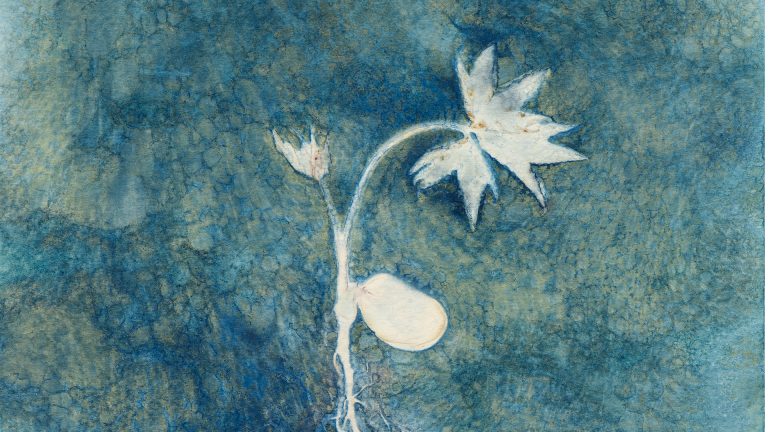

Like most spring bulbs, snowdrops have evolved two ways of propagation.

The flowers are pollinated by insects, bumble bees playing a particularly important role as they are among the first pollinators to appear and are able to fly in cooler temperatures from about 10°C. As spring temperatures in the British Isles frequently fall below this threshold, this sexual form of propagation through seed production is often unreliable.

However, interestingly, ants have a role to play in this as well. Attached to the seeds is a fleshy, sugary tail, the elaiasome, which is attractive to ants, who carry the seeds below ground and help to distribute and plant them.

First, the outer flower segments wither until eventually all segments fall off, leaving just the ovary behind. In the centre of the second image you can make out the pollen stained filaments and anthers. If the flower was pollinated, the seeds will now begin to ripen in the ovary.

The second method of propagation is vegetative. The bulbs produce genetically identical bulb offsets, which is why snowdrops often grow in closely packed groups. The best time to divide and replant these groups is ‘in the green’ when the flowers have withered, but the leaves are still green.

True Survivors

Snowdrops are among the first flowers to emerge in Spring and are perfectly equipped to cope with the extreme conditions at the end of Winter. When temperatures drop they start to produce glycerin instead of glucose.

Snowdrops produce glycerin, which protects them from freezing. That’s how they can withstand pretty extreme temperatures.

Glycerin acts a bit like antifreeze. It lowers the freezing point, therefore preventing the freezing and expanding sap in the cells from bursting the cell walls and effectively killing the cells and potentially the entire plant.

Snowdrops are incredibly resilient. After several weeks of snow and temperatures below freezing, there was a sudden thaw at the end of February followed by rain and many of the local rivers and burns burst their banks. (see the short video below)

Countless snowdrops along the banks were flooded for several days and had to withstand the raging river flow. But they survived that as well! On my daily lockdown walk I had the chance to observe developments more closely than ever before and was astounded to witness just how tough these delicate snowdrops really are.

Receding flood

The whole is more than the sum of its parts – Aristotle

So, what makes them so special? Is it simply the facts I have listed above?

Yes and No! Of course I am constantly amazed at how well snowdrops are adapted to the harsh conditions during their precarious emergence on the cusp of spring.

Ultimately though they are a very welcome first spark of life at the end of a long winter and I just love the simple, graceful elegance of these deceptively fragile plants. So each and every spring, I guess that’s what makes me turn up to our earliest possible photographic rendezvous without fail.

Find out more about what to bear in mind when taking close-up images of snowdrops in the second part of my ‘Homage to the Snowdrop’.